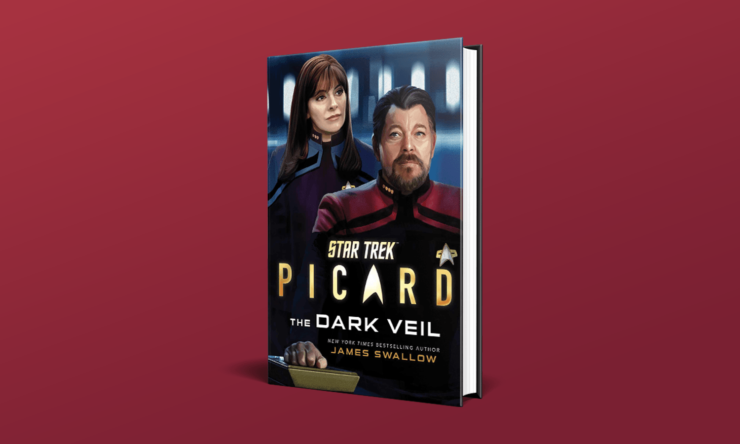

Star Trek: Picard: The Dark Veil

James Swallow

Publication Date: January 2021

Timeline: 2386

This media tie-in is a superlative accomplishment.

Regardless of your level of enthusiasm for Star Trek: Picard, if you have any interest at all in the future of the Trek universe in the wake of Star Trek: Nemesis—specifically, the fates of William Riker, Deanna Troi, and yes, albeit tangentially, Jean-Luc Picard himself—you must read this book.

I went in having watched, and re-watched, key moments of Picard, and having read and written about the first Star Trek: Picard novel, Una McCormack’s The Last Best Hope. While that knowledge certainly enhanced the reading experience of Swallow’s exemplary work, none of it is needed to have a thoroughly good time.

In fact, that’s a particular point of praise with which to begin this conversation. Given the enormous weight of 24th-century Trek continuity, and the multiple concurrent Star Trek series in production that keep adding to its fabric at different points of the timeline, writing an entertaining, emotionally captivating novel that ties in to many of these elements but can be essentially enjoyed as a self-contained standalone is a praiseworthy feat in and of itself.

The preceding volume, The Last Best Hope, was published partway through the first season of Picard, and artfully complemented what had been established on screen at the time by fleshing out interesting backstory. In terms of chronology, the series Picard kicks off in 2399; The Last Best Hope unfolded between 2381 and 2385, making it a prequel to the show; this book is set in 2386, so it’s a sequel to the first prequel book but still a prequel to the series. As the cover makes clear, this novel concerns itself with the crew of the U.S.S. Titan, captained by William Riker. It also features a variety of Romulans, and a fascinating new alien species called the Jazari. This novel’s prequel status could theoretically deflate its tension, but it manages to be consistently thrilling.

Buy the Book

Star Trek: Picard: The Dark Veil

Per Nemesis, Riker takes command of the Titan in 2379, seven years prior to this novel’s events. Our story opens with Riker being held in a cell by Romulans aboard a warbird and then ushered into a tribunal chamber. Present are Major Helek of the Tal Shiar, represented by the tribune Delos; Commander Medaka, captain of the warbird Othrys, represented by the tribune Nadei; and Judicator Kastis. Riker begins to explain the mission that brought him to this point, and we jump back six days earlier, taking us into the extended flashback that comprises the novel’s bulk. Riker himself, incidentally, is also given a tribune, but this figure remains deliberately cloaked until the book’s end, and I’d rather not spoil that surprise.

The Titan, we learn, was escorting a group of diplomats from an incredibly reclusive but firmly polite alien race, the aforementioned Jazari, back home to their star system, near the Romulan Neutral Zone. One Jazari named Zade has actually been serving aboard the Titan as a Lieutenant (the Federation has been in contact with the Jazari for about a century), but even so, very little is known about them. As the Titan reaches its destination, the crew observes that the Jazari homeworld seems stripped of all life, appearing “cut open and cored.” Lieutenant Zade makes a comment about “the work” being completed, and the Titan ascertains that the Jazari have built a massive generation ship. Claiming that they no longer feel welcome in this sector of space, they are about to embark on an exodus. Zade, resolved to join his people on this stellar journey to an undisclosed location, resigns his Starfleet position.

Still, despite this somewhat dramatic turn of events, and becoming aware of the Othrys in de-cloaked status right across the Neutral Zone, it’s been a pretty quiet mission for the Titan—until a massive accident aboard the smaller Jazari vessel Reclaim Zero Four causes all hell to break loose. An extremely dangerous subspace fracture opens up, and its effects batter the Titan, and more gravely, threaten the stability of the generation ship. Eventually, the Titan, with surprise help from the Othrys, reverse the Zero Four’s anomaly, but not without taking a severe beating in the process. Much of the Titan becomes temporarily uninhabitable, with days-long repairs underway. In exchange for their help, the Jazari offer sanctuary to part of the crew in one of their generation ship’s ecodomes. As the generation ship’s route will take them through a treacherous region of space that the Romulans have superior intel on, it’s agreed that both the Titan and the Othrys will both follow along the generation ship’s vector for forty-seven hours. During this time, Riker and the Romulan Commander of the Othrys, Medaka, have a wonderful exchange, lamenting that the temporary alliance between their peoples during the Dominion War did not lead to a more long-lasting camaraderie, and reflecting on the Romulan’s impending supernova disaster and the Federation’s retreat from its evacuation assistance efforts following the 2385 synth attack on Mars and its orbital shipyards.

The fragile three-ship/three-power triangle is soon disrupted. Riker and Troi’s young son, Thaddeus, aboard the generation ship’s assigned ecodome, ventures where he shouldn’t, befriends a drone that seems to represent a sentience named simply Friend, and is grounded for his behavior. Aboard the Romulan vessel, we learn that Major Helek is, beneath the Tal Shiar sheath, working for the Zhat Vash (the same organization that covertly orchestrated the synth Mars attack). Helek’s illegal spying on the Jazari generation ship seems to suggest that the Jazari are harboring active positronic matrices. The Zhat Vash, based on their Admonition, abhor all artificial lifeforms and strive to eradicate them, so Helek is commanded to find out where these positronic brains are and destroy them. She and one of the Othrys’ crew, in search of answers, capture a Jazari scientist. Meanwhile, Thad has snuck off again, trying to convince the adults of the existence of Friend, and ends up getting critically injured through a detonation that is part of the Romulan subterfuge designed to mask their kidnapping as an accident. With Thad in a coma, Helek tortures the Jazari captive for information, and in the Jazari’s ensuing struggle for freedom, a far-reaching secret comes to light.

Following this, the action escalates quickly: a way must be found to save Thad, while the Othrys—now under the control of Helek, who has ousted Medaka and painted him as a traitor to the Federation—turns on the Titan and the Jazari. Plans are improvised and characters are tested—you know it’s serious when Riker calls on Admiral Picard to get his perspective on the situation—on the way to a nail-biting action finale. This is followed by a clever inversion on the way these things usually pan out, with the Federation itself getting uber-Prime Directive-ized, and a melancholy farewell to the Jazari. The tribunal from the opening chapter then resumes, with us readers privy to more than what is officially disclosed. The conclusion is satisfying and smile-inducing.

In the Picard episode “Nepenthe”—spoiler warning—we discovered that Riker and Troi gave birth to Thaddeus in 2381. Thad would go on to suffer from a rare silicon-based disease, and might have been cured by means of a positronic matrix. Because of the 2385 synth Mars attack, however, Starfleet had banned synths and positronic matrix research, ultimately making Riker and Troi’s situation a lost cause. They also had a daughter named Kestra, whose birth is announced in the pages of this book, and who is alive and well as of 2399. For me, the foreknowledge of Thad’s eventual death imbued his adventures and close call here with additional layers of pathos and tragedy. At the same time, without getting into the details of the situation, the events chronicled in The Dark Veil help implicitly clarify the relationship between Thad’s subsequent disease and the possibility of a positronic-matrix-tech-related cure (which had struck me as overly contrived when watching the episode).

This brings me to a second group of elements in this novel, beyond its admirable standalone-readability, that I’d like to commend: storytelling execution, attention to detail, and continuity. The opening and closing tribunal sections provide a clever, effective way to immediately engage our attention and frame the narrative. It’s also refreshing to encounter scenes told entirely from the Romulan perspective (e.g., Chapter Four) and, even more intriguingly, from the Jazari point of view (e.g., Chapter Five). Every time a problem or crisis arises, characters handle it smartly, exploring all the options one might reasonably wish to see them investigate (e.g., using a reflection pulse from the external sensors when the internal sensors are down). There are tons of elegantly tucked-in references, so that nothing feels arbitrary or jarringly inserted after-the-fact.

Since I was just talking about Thad, we may as well start with him. Everything we learn about him here, including his middle name being Worf, seems to be consistent with a backstory that was elaborated for the series and only recently revealed online. At one point, we’re told that, “Along with his Kelu project, he [Thad] already knew enough French to read the copy of Le Petit Prince that Jean-Luc Picard had given him as a birthday gift”—this establishes a nice link with The Last Best Hope, in which Picard had recited lines from said book to Elnor. The following lines by the Titan’s doctor also suggest that the genesis of Thad’s disease likely lies in the technique used to save his life in this novel: “‘Theoretically, neural sequencing of the affected areas of the patient’s brain would mean a greatly improved survival ratio,’ allowed Talov, ‘but it also carries the inherent probability of complications in later life. The effects are… unpredictable.’” Indeed.

I mentioned the Dominion War, which is rightly alluded to several times, as befits an event of that magnitude. The Star Trek: Lower Decks finale isn’t ignored: “Troi sighed deeply. ‘No one is going to forget the Pakled delegation’s visit in a hurry.’” A few other of my favorite episodic callbacks include “The Enemy” (Picard is writing a historical work about Station Salem-One), “Who Watches the Watchers” (“In their time on board the Enterprise, her husband had undertaken that exact assignment on a world called Malcor III, and together they had both disguised themselves as members of a proto-Vulcan species during a mission to a planet in the Mintaka system”), “Face of the Enemy” (“Riker’s wife knew the Romulan character better than anyone in the room. She’d even lived as one of them for a brief period, taking on the identity of one of their Tal Shiar intelligence operatives during a clandestine mission behind enemy lines”), “In the Pale Moonlight” (the same “It’s a fake!” line riffed on in the Rules of Accusation novella I recently reviewed), a follow-up on Anij and the Ba’Ku from Star Trek: Insurrection, and one that filled me with giddy delight: the application of a “static warp shell” by two vessels simultaneously to seal the subspace fracture that sets all these events in motion, an homage to “All Good Things”.

But there’s another aspect of the continuity that will likely please certain cadres of readers. Swallow incorporates characters and ships from the pre-existing Trek “litverse,” in effect now bringing them to life in the new canon. No doubt made possible by close work with Kirsten Beyer and other current franchise insiders, Swallow seamlessly blends the post-Nemesis continuity we’ve seen so far in the Picard: Countdown comic books, Picard itself, and The Last Best Hope, with a few hand-picked pre-existing elements from the literary works that had already charted some of these same years. Besides Riker and Troi, here’s the Titan’s senior crew as established in this novel:

- Riker’s exec is Commander Christine Vale (a character who appeared in the Titan novel Taking Wing by Michael A. Martin and Andy Mangels, as well as many other prior works of the Trek litverse)

- Lieutenant Commander Keru, an unjoined Trill, serves as Titan’s senior tactical officer (also appeared in Taking Wing and other books)

- Karen McCreedy as the Chief Engineer (appeared in the Titan novel Synthesis, also by James Swallow)

- Lieutenant Commander Jonathan East; the ship’s (Irish) security chief

- Doctor Talov, the Vulcan chief medical officer

- Lieutenant Cantua, a Denobulan helmswoman

- Lieutenant Commander Livnah, a senior science officer (whose race and name suggest a kinship with Jaylah from Star Trek: Beyond)

Two ship references I noted, in line with this litverse approach, are the Lionheart (see Swallow’s The Fall: The Poisoned Chalice) and the Robinson (Sisko’s eventual command post in novels I’ve reviewed, like Typhon Pact: Rough Beasts of Empire or Sacraments of Fire). There are more esoteric references, like the Taurhai Unity, which stem from various games, manuals, etc. In short, Swallow has been extremely thoughtful in his selection of the Titan’s crew and its backdrop. The Othrys also boasts a variety of non-Romulan aliens, which doubles as a comment on Medaka’s philosophy.

In terms of the macro-backdrop of the Romulan supernova, this novel heavily suggests that a Romulan scientist named Vadrel may have been—alone or with others working in secret alongside him, and directed or at least monitored by the Tal Shiar—responsible for it. So, perhaps unsurprisingly, the Romulans may turn out to be the victims of their own epic-scaled hubris. Whoa.

One ongoing issue with the underlying architecture of the supernova-related plot (not something specific to this novel or the first one in this series) established in Star Trek (2009) and sort of re-explained in Picard is that events that technologically dwarf the complexity of that problem’s resolution continue to happen regularly. For instance, in this story we encounter beings with access to an awe-inspiring level of technology. They can burrow through spacetime from one galaxy to another. Unless I missed it, it would have been nice for Riker, when hit with these revelations, to say something like, “Gee, I know there’s not a chance in hell you’ll agree to this, but could you help us out with some tech that might prevent this one specific star from going nova? You don’t even need to tell us the secrets of whatever you do! Or if that’s too tall an order, could any of your magic tech be deployed to save a couple more billion lives than what we’ll likely manage?” Yes, these attempts are bound to fail, but it would be nice to acknowledge the technological consistency of these ideas.

The third and final aspect of the novel I want to highlight is its inherent optimism. As mentioned in my Last Best Hope review, I’ve found the Picard-future, in some ways, troublingly dispiriting when directly compared with earlier incarnations of Trek. “Optimistic, ensemble-driven problem-solving is at the heart of what I’ve most enjoyed during several decades of Trek,” I wrote back then, and this book brims with exactly that spirit of can-do optimism, specially when the situation is most dire. The non-regular characters, particularly Medaka and Zade, shine. Laris and Zhaban have a few neat little moments with Picard. Riker and Troi themselves are extremely well fleshed-out, their voices captured perfectly. This story visibly deepens them, too. In some ways, like the narrative handling of Thad’s near-death situation, the growth and characters arcs are clear. But there are more subtle instances too, like the beautiful parallel that arises with the Romulan evacuation when Riker has to decide whether or not to risk his own ship, family, and crew to help the Jazari:

And then it came to him: Was this how it had been for Picard? Not just during the Enterprise’s missions, but when the Romulan crisis began? Knowing that they were about to put their all into a desperate gamble to save a civilization, with no guarantee that their endeavor would succeed. But it had to be done. To turn away would be unacceptable.

The recurring theme that makes many of the character dynamics memorable is a classic one of forgiveness and the ethical imperative of learning to trust for the greater good. The crew of the Titan must trust the Romulans; Medaka’s long-serving crew must trust him again after being fed very convincing lies by Helek; the Jazari must trust both the humans and Romulans initially, then even more so the humans once a key secret is exposed, and so on. The title’s veils are dramatically enacted. One such is “the veil between two cultures held closed for centuries,” namely the Federation and Romulan Empire. Another is the Jazari veil:

“We have kept a truth from the galaxy for over one hundred of your years,” said Yasil. “In order to carry out our grand project, and so we might protect ourselves, we created a fiction. […] “Now that veil has been torn away, for better or for worse, and we are left to decide what happens next.”

Medaka also makes an excellent point about appearances versus reality:

The Federation knows that our charts of the Star Empire’s borders are exacting in detail, even those of areas that by treaty we should never venture into. They ignore that truth the same way we ignore their listening posts disguised as astronomical observation platforms. The veil over these things is a convenience.

The book is easily quarried for quotes that capture the classic Trek ethos of a brighter, more profoundly humanistic future. Consider, for instance, these aspirational words by Riker: “We are also dedicated to reaching beyond the boundaries of what we know. Our first, best impulse should always be to hold out the hand of friendship. Not close our doors and bar the gates.” Later, Riker again: “The United Federation of Planets isn’t perfect, but we’re open about our record. Our coalition, as you call it, is founded on the ideals of friendship and cooperation among all sentient life.”

Because of this novel, some of my favorite Picard moments now unfold on the page, rather than on the screen. The Dark Veil sets an incredibly high bar for any future Titan– or Picard-related outings, regardless of medium, and provides ample proof that Star Trek doesn’t need to be re-invented in order to enthrall and inspire. One of my favorite lines in this story is Riker’s statement of purpose during a moment of self-doubt: “We move forward and we do what good we can.” With this novel, Swallow shows us precisely how.

Alvaro is a Hugo- and Locus-award finalist who has published some forty stories in professional magazines and anthologies, as well as over a hundred essays, reviews, and interviews.